Women make history every day! In Ontario County, I am reminded about some of our historical women through the architecture I see, the artwork I admire, and the stories I hear on a regular basis. Here are 5 amazing women associated with Ontario County!

Jikonsaseh, also known as The Mother of Nations (no known date)

Jikonsaseh was a powerful Haudenosaunee woman who was a key player in the formation of the Iroquois Confederacy. The short history that follows is based on a story shared with me by Tonia Galban, an interpreter at Ganondagan State Historic Site in Victor (pictured at right).

Before the Confederacy, there was much conflict among the Cayuga, Seneca, Oneida, Onondaga and Mohawk peoples. When The Peacemaker (also known as Deganawida) first brought his vision of unifying these nations, he had many obstacles to overcome. The Mohawks pledged to put down their war weapons only if their brothers to the west agreed as well. So The Peacemaker made his way west, addressing challenges with each group.

The first person to embrace The Peacemaker’s message was Jikonsaseh. After testing his mind and words, she agreed to join The Peacemaker on his quest. The Peacemaker also relied on Ianwenta (also known as Hiawatha), a talented communicator who became an ardent follower of The Peacemaker’s message.

The last chief to be persuaded to make peace among the five nations was Tadodaho, an Onondaga Chief of great power who ruled his people with a bad mind. The Peacemaker and his allies gathered at Onondaga Lake, trying to assuage Tadodaho with singing and wampum and commitments to make him the First Chief of 50 Confederacy Chiefs. They were able to smooth his snake-like hair and straighten the crooks in his body by calming his mind with the song of the Hi:hi and the words of Kienashekowa. With Jikonsaseh’s guidance, The Peacemaker and Ianwenta turned the Onondagas into the “firekeepers” of the Confederacy.

Jikonsaseh and Ianwenta are credited for establishing the rights and responsibilities of male and female leadership roles in the Iroquois Confederacy. Jikonsaseh became known as the Mother of Nations, and her title is passed down through generations. While there are gender-distinct roles of leadership divided between men and women, women have equal responsibility in Haudenosaunee/Iroquois society.

Sarah Hopkins Bradford (1818-1912)

You most likely know the story of Harriett Tubman, the escaped slave who risked her life over and over again, returning to the South to help hundreds of other slaves reach freedom in the North via the Underground Railroad. Tubman’s remarkable achievements did not stop there. During the Civil War, she worked as a cook, nurse, scout and spy for the Union Army, and when she finally settled in nearby Auburn, New York, she made her home a place of care for elderly African-Americans.

You likely wouldn’t know anything about this if it weren’t for Tubman’s biographer, Sarah Hopkins Bradford. The famous children's book author lived in Geneva, and was known for her “Sunday School” books that taught moral lessons to youngsters. In the late 1860s, at a time when Tubman was struggling to keep her house in Auburn as she was denied a pension for her military service, a group of supporters came up with a plan: find a skilled writer to write Tubman’s biography, sell it by subscription and allow the proceeds go to Tubman.

This group solicited Bradford to write the book, and that is how “Scenes in the Life of Harriet Tubman” was published in 1869. The book was followed by a second, “Harriet Tubman, Moses of Her People.” Bradford, an abolitionist, conducted many interviews with Tubman, who could not read, and the two formed a friendship.

Bradford’s Geneva home (pictured below), at 629 South Main Street, is now the admissions office for Hobart and William Smith Colleges. The Adobe in Gothic Revival house was built in 1840, and the Bradfords were the first owners. After her husband's death in the 1850s, Bradford ran a school here that was called Mrs. Bradford’s School for Young Ladies and Little Girls.

Elizabeth Blackwell (1821-1910)

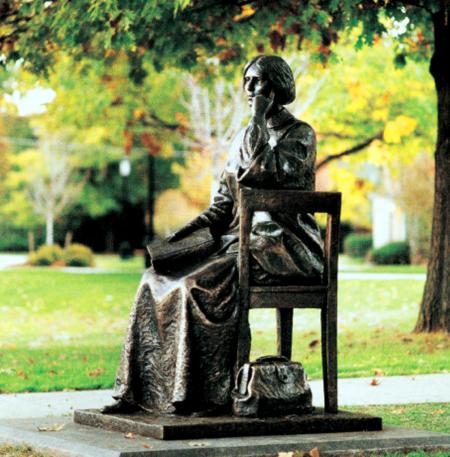

If you spend any time in Geneva, you will likely come across historic markers and public art that recognize Elizabeth Blackwell, the first woman in the United States to receive a medical degree. Blackwell graduated from Geneva Medical College (the predecessor to Hobart College) in 1849. She was 28 years old.

Born in England but raised in Ohio, Blackwell knew early on that she wanted to pursue a career in medicine. She taught school as a way to raise tuition money and applied to more than two dozen medical schools. Geneva was the only one to accept her, but it did so as a joke. The faculty in Geneva were uncertain about accepting a woman, so they put Blackwell’s application out as a vote among the 150 male students. They voted unanimously to let her in, not thinking she would actually show up for classes.

That was only the first of many obstacles she had to overcome. It was hard to find housing as neighbors looked upon her with suspicion, anatomy lessons could be shockingly crude and unwelcoming, and fellow students often treated her with disdain. But when she was handed her diploma in 1849, the dean bowed to her, the press wrote about her with admiration and the citizen of Geneva flocked to her residence to congratulate her. She had the best academic record of her class.

Blackwell’s time in Geneva was short, but the legacy she leaves is very long. She continued her medical studies in Europe and then opened a dispensary in New York City. In 1857 she and her sister Emily, the third woman in the United States to receive a medical degree, opened the New York Infirmary for Women and Children. By the time Blackwell died in 1910, she had left her mark as a well-traveled social reformer and activist, had written essays and books and founded the National Health Society.

A bronze statue of Elizabeth Blackwell can be found on the campus of Hobart and William Smith Colleges. It was created by art professor Ted Aub and dedicated in 1994.

Susan B. Anthony (1820-1906)

When you think of the pioneers of American women’s suffrage, Susan B. Anthony’s name is at the top of the list.

Born into a Quaker family with strong abolitionist convictions in Massachusetts, Anthony was teaching school in Canajoharie, New York, when the first Women’s Rights Convention took place in Seneca Falls in 1848. A few years later she was fortuitously introduced to Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who would become her lifelong friend and sister soldier in the fight for the vote.

Anthony settled in Rochester and dedicated herself to many causes: abolition, labor, temperance and women’s rights. But it was suffrage that became her life work. In November 1872, Anthony, three sisters and a few other women registered to vote in Rochester, and then voted in the general election in which Ulysses S. Grant was elected for a second term as president. She was arrested several days later.

Her trial took place at in Canandaigua in June 1873 because the Rochester District Attorney was concerned that the jury would be too sympathetic to Anthony. The judge overseeing the Canandaigua trial steered that jury to convict her without discussion. She refused to pay the $100 fine, but the judge did not throw her in prison in order to keep her from appealing.

The courthouse where Anthony was tried still stands, though the room where that trial took place is long gone. You can see Lady Justice standing proudly on top. Sadly, Anthony did not live long enough to see the 19th Amendment giving women the right to vote ratified. But with the statue of Lady Justice looking down on Canandaigua from the courthouse, you feel that Anthony’s legacy is one that has changed the world forever.

Eunice Newton Foote (1819 - 1888)

A major topic of discussion in our current world, the Greenhouse effect, was discovered by Eunice Newton Foote! Foote is a relatively unknown American scientist, inventor, and women's rights activist. She came to Ontario County in 1820 with her parents and siblings, who settled in East Bloomfield. Some people speculate that her interest in women rights activism, science, and abolitionists came from the culture of the Finger Lakes region, as well as being a distant relative to Isaac Newton.

Foote attended the Troy Female Seminary, a pioneering school in women's education that was established to teach pupils dance, history, languages (English, French, Italian, Latin), literature, mathematics (general, algebra, geometry), music, painting, philosophy, rhetoric, and science (botany, domestic science). Some of these studies were provided by the nearby Rensselaer School.

On August 12, 1841, in East Bloomfield, Newton married Elisha Foote Jr., a lawyer who studied under Judge Daniel Cady, the father of women's rights activist Elizabeth Cady Stanton. They then moved to settle in Seneca County, where she was neighbor and friends with Stanton herself. Foote and her husband Elisha were signatories of the convention's Declaration of Sentiments that demanded women's social and legal rights equal to those of men, as well as the right to vote. Foote was one of the five women who prepared the proceedings of the convention for publication.

In 1856 Foote published a paper that summarized her research surrounding the effect of sunlight on carbon dioxide gas. From this research she was the first scientist to conclude that rising carbon dioxide levels resulting from emissions would impact our climate through changes in our atmospheric temperature caused by CO2. This is now commonly known as the Greenhouse effect, and in the years since, we have seen Foote's predictions come to life.